The second voyage of discovery: Introduction–––Official instructions–––Routine tasks, navigation & acting–––Tide observation incident–––Charity, fishing & Crozier River–––The third voyage–––The North Pole–––Parry & Crozier

Parry's second voyage of discovery

W. Edward Parry’s first voyage in search of the North West Passage (1819-20) was a triumph, but the ultimate goal – a complete traverse of the Passage – was not achieved. A second attempt was thus mounted in 1821. An identical ship was outfitted to accompany the proven Hecla instead of the unsuitable Griper (Parry, p. iii), and the crew was augmented accordingly. Of the eight midshipmen, three had advanced to lieutenant, and two didn't continue. There was no lack of volunteers wishing to join the experienced explorers, but the criteria were very strict. Crozier was selected to become one of the five new midshipmen, and he joined his future friend James Clark Ross on the new flagship, the Fury.

Aside from the usual duties, Crozier was employed in leading the hunting and fishing parties. There were also various ad hoc tasks, and he did a spot of botany. Together with the other crewmen he assisted the Inuit and spent some time observing their habits. It appears he didn't take part in any multi-day scouting trips, though once, rather memorably, he was despatched to perform a scientific observation. Right before the expedition turned round, with the list of dignitaries and crew near exhausted, Parry named a river they’d been fishing in after Crozier.

Official instructions

Objectives, in order of importance:

- to discover a passage by sea between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans;

- to ascertain the geography of North America;

- to make scientific observations.

Route:

- Parry is ordered to head for Hudson's Strait, clear Nautilus transport, enter westward through the Strait seeking Repulse Bay or other continental parts of coast north of Wager River and proceed north examining every passage-like inlet. If no route is found during the first season, Parry is to decide whether to return for a refit or to overwinter.

- If a route is discovered, he is to proceed without stopping/exploring, unless checked by ice or similar. Reaching the Pacific Parry is to proceed to Kamchatka to deliver copies of journals, and then continue to the Sandwich Islands or Canton to refit, before returning home.

- If the passage is not accomplished before autumn 1824, a ship with provisions is going to be despatched eastward via Behring's Strait.

- If Parry chooses to overwinter, he is to find a safe harbour and take care of the health and comfort of the crews. If he meets native people, he is to cultivate a friendship with them by making presents, but also remain on guard in case of hostility.

- Should Parry reach the Coppermine River area, information is to be deposited on shore for the Franklin expedition; he is also permitted to take them to England if desired.

- Parry is advised against the ships separating, and communication between them is encouraged. In case of one ship becoming disabled, the officers and crew are to be removed to the other, either to return or to continue, according to the circumstances. If the Fury is the one affected, Parry is to command the Hecla; if Parry perishes, Lyon is to take the command of the expedition from either the Fury or the Hecla.

Scientific goals:

- To make observations of the variation and inclination of the magnetic needle; the intensity of the magnetic force; the effect of the atmospherical electricity and the Aurora Borealis; the air temperature and the sea temperature at different depths; the refraction and meteorological phenomena; the tides and the currents; the depth and the floor of the sea;

- To make charts and to take views of the coast;

- To collect and preserve as many specimens of the animal, mineral and vegetable kingdoms as can be stowed on board.

(Parry, p. xxi)

Main events in chronological order. All quotes Parry, unless noted otherwise. With annotations

Routine tasks, navigation and acting

1821

• The expedition has passed Hudson's Strait and arrived at Southampton Island (Shugliaq). Parry, forgoing Roes Welcome, is looking for the eastern entrance to Frozen Strait

Aug 16

While engaged in beating through the channel [between Southampton Island's Cape Welsford and Nias Islands] with a considerable tide against us, I despatched Mr. Crozier to bring on board sand for the decks, and provided him also with nets for catching sillocks [*], of which he procured enough to serve the messes of the officers and ships' company for two dinners. (p. 40) [Map 2: 1.]

Note:

* James Clark Ross: 'Merlangus Polaris' [accepted name Boreogadus saida, polar or Arctic cod] It is this fish which Captain Parry mentions in the narrative of his second voyage, as having been collected in great numbers from the pools left by the falling tide, on the rocks at the entrance of the Duke of York's Bay. /See page 39/ They are very numerous in all parts of the Arctic Regions visited by the late Expeditions. (Appendix: Natural History / Zoology / Fishes; Parry III, p. 110) (image)

|

1821 Papaver Nudicaule [Iceland Poppy] Winter Isle |

• In October the temperature drops, it starts snowing, and the ice advances (Fluhmann maintains [p. 17] that Crozier was delegated to examine the area

around the Bay of Shoals – which they passed after waiting out a gale in

Safety Cove). Finally they're forced to shelter at the SE point of Winter Island (Neyuning-Eit-dua). Parry sends men ashore to sight the conditions ahead

Oct 7

At daylight on the 7th I despatched Mr. Crozier to the point, beyond which, at the distance of one mile, he found the whole body of ice close in with the land, appearing very thick and heavy as far as could be seen to the north-eastward. (p. 115) [Map 2: 2.]

• The season is over, there's still coast to explore, so the ships are prepared for the winter. The heating of the interiors starts, the decks are covered with housing-cloths, an observatory is built on shore. Winter rations and exercise regimes are established, a school is organised, a joint divine service for all men aboard the Fury is agreed, and “Theatre Royal” opens with a performance of Sheridan's 'The Rivals' in November, Crozier playing Sir O'Trigger

Note:

Sir O'Trigger is a "fire-eating" (CODEL, p. 446),

impecunious Irish nobleman who pursues his love and falls victim to the ladies' schemes. In the first version of the play that Sheridan rewrote the character was a crass caricature of an Irishman

|

| The playbill (Lyon, p. 92) |

Sheridan: It is not without pleasure that I catch at an opportunity of justifying myself from the charge of intending any national reflection in the character of Sir Lucius O'Trigger. If any gentlemen opposed the piece from that idea, I thank them sincerely for their opposition; and if the condemnation of this comedy (however misconceived the provocation) could have added one spark to the decaying flame of national attachment to the country supposed to be reflected on, I should have been happy in its fate, and might with truth have boasted, that it had done more real service in its failure, than the successful morality of a thousand stage-novels will ever effect. (source)

1822

• The overwintering is proceeding smoothly. On Feb 1 a group of Inuit arrives, intending to catch seals (the summer supplies have failed). The ships' crews and the Inuit exchange visits and establish a relationship, trading articles and entertainments. The ships support the locals with food, water, and medical assistance, such as bleeding and blisters. Another group follows in the footsteps of the Inuit

Feb 17

Mr. Crozier, who visited the huts, found that the Esquimaux, as well as ourselves, had been induced to attempt the destruction of their followers, the wolves, by setting a trap for them not unlike ours, except in the materials, which consisted only of their staple commodity, ice. (p. 173)

• In spring, inspired by the charts of the coast drawn by the Inuit, the expedition starts preparing for the approaching season. Captain Lyon is despatched on a reconnaissance trip over land in May. First casualties occur. James Pringle, sent back from said trip early, falls to his death from the Hecla's mast. On Jun 3 the work starts to cut the ice in order to free the ships. Before the nature assists the expedition out of its winter quarters, two of the Fury's men die of illness

• The ships weigh anchor on Jul 2, and the second season begins. After an eventful passage north that includes both a minor collision between the ships and an outing to a waterfall, they reach Igloolik (ᐃᒡᓗᓕᒃ) on Jul 16. There they meet a barrier of unbroken winter ice and befriend a new group of Inuit

Note:

Throughout, Parry

seemed oblivious of the fact that his insistence on giving things gratis (pp. 271, 424), failure to maintain some fairness of the trade (p. 162), and varying rewards for services rendered were unbalancing the

traditional barter system, and that it's likely causing the issues he's railing against.

Lyon meantime approached the foreign culture from various angles and was curious about the Inuit; he gamely tried everything from local food to

tattoos. Among the things that impressed him was how well-behaved the

children were compared to their spoiled English peers (Lyon, p. 119).

• They spend some time exploring the waters of the new region. As they're returning to Igloolik, Crozier notices that a local magnetic attraction on land is affecting the ship’s compasses

Aug 1

Just before we reached the edge of the floe the weather continuing extremely thick with hard rain, I desired Mr. Crozier to set the extremes of the loom hanging over Igloolik, which was then on our lee quarter. He accordingly did so, but presently afterwards remarked that the compasses, (both Walker's azimuth and Alexander's steering,) indicated the ship's head to be S.W., which was about the middle point on which, but a few minutes before, he had set the loom of the land two or three points abaft the beam. [...] Being now obliged to tack for the ice, we carefully watched the compasses in standing off, and having sailed about a quarter of a mile observed them both gradually return to their correct position. Being thus satisfied that some extraordinary local attraction was influencing the needles, we again tacked to repeat the experiment, and with a nearly similar result. (p. 297)

• With the ships berthed at the ice edge off Neerlonakto (now Nirlirnaqtuuq, ᓂᕐᓕᕐᓇᖅᑑᖅ), Parry sets out to scout the elusive strait on foot, and Crozier is assigned to the fatigue party

Aug 14

My party consisted of Mr. Richards, and two men from each ship, and we were furnished with ten days' provision. Mr. Crozier, with three additional men, was appointed to assist in carrying our baggage to the first islands, and then to return on board. [...] I left the ships at half-past one P.M., but had scarcely proceeded two hundred yards, when we found that a plank would form an indispensable part of our equipment, for the purpose of crossing the numerous pools and holes in the ice. Two planks of fir nailed together being speedily furnished from the ships, at two P.M. we finally took our departure. [...] we made quick progress to the westward for seven or eight miles, when the holes and cracks began to increase in frequency and depth, and we were three hours in accomplishing the last mile and a half [...] We landed at a quarter past nine P.M. after seven hours' walking, the direct distance from the ships not exceeding ten or eleven miles [...] (pp. 307-308)

Aug 15

The difficulty experienced in landing made me apprehensive lest Mr. Crozier and his party should not be able to get from the island without the assistance of our bridge. I despatched him, however, at four A.M. on the 15th, and had the satisfaction to find that being now unencumbered with loads, he and his men were able, by a circuitous route observed from the hills, to leap from one mass of ice to another and thus to gain the more solid floe. Having seen him thus far safely on his way, we crossed the island one-third of a mile to the westward [...] (p. 308)

I learned from Captain Lyon that Mr. Crozier and his party had scarcely got on board the ships when the weather became extremely thick and continued so all night, so that his return was very opportune, and the more so, as on the following morning the whole body of western ice, including that to which the ships were attached, was observed to have broken up. (p. 315)

• With the ice letting up, the ships proceed north-west. Another compass irregularity occurs on Crozier's watch as they're approaching Cape North-East

Aug 26

The wind gradually falling was succeeded by a light north-easterly breeze, with which at daylight on the 26th we steered under all possible sail up the Strait. The course being shaped and no ice in our way, I then went to bed; but was immediately after informed by Mr. Crozier that the compasses had shifted from N.1/2E., which was the course I left them indicating, to E.1/2N., being a change of seven points, in less than ten minutes. (p. 317)

The tide observation incident

• The ships meet yet another barrier of ice, now in the freshly named Fury and Hecla strait. While at anchor near Liddon Island (now Saglirjuaq, ᓴᒡᓕᕐᔪᐊᖅ), three new scouting parties are despatched to look for options (Capt. Lyon, Lt. Palmer, Lt. Reid). The depleted resources do not stop Parry from sending Crozier out to ascertain whether there's a permanent current in the strait

Aug 30

I determined therefore on despatching Mr. Crozier on this service; and the absence of so many of our people necessarily limiting our means, his establishment only consisted of the small nine-feet boat and two marines, with which he left us under sail at one P.M., being provisioned for four days. I directed Mr. Crozier to land and pitch his tent somewhere about Cape North-East [Map 3: 3.], and after carefully observing the tides, both on shore and in the offing, for the whole of one day, immediately to return to the ships. (p. 324)

However, two days later the weather turns

Sep 1

The north-west wind freshening almost to a gale, which made me somewhat apprehensive for Mr. Crozier and his little establishment at the Narrows, I despatched Mr. Ross, at seven this evening, to carry him a fresh supply of provisions and to assist him on his return to the ship. At the same time I directed Mr. Ross to occupy the following day in examining the portion of land […] (p. 328)

The same day, Lyon returns from his unsuccessful scouting trip and reiterates

Sep 1

Lyon: Captain Parry informed me, that he had sent Mr. Crozier in our small boat, with two men, to make observations on the current in the strait. They were provisioned for four days, but on that of my return, as it blew hard from the N. W., another boat was sent with a farther supply, and her officer was then to examine the northern shore of the narrows. (p. 268)

Equipped with a more suitable gig, Ross arrives at Crozier's position to discover them adrift and with little chance of reaching the shore on their own. Ross saves Crozier and his men by towing them in

[retrospectively] […] they had encountered no small danger, while attempting to try the velocity of the stream in the narrows, being beset by a quantity of drift-ice from which they with difficulty escaped to the shore. I found also that Mr. Ross, after towing them in when adrift ["under circumstances of considerable danger to that gentleman's party in their little boat" p. 337], and leaving Mr. Crozier his provisions, had proceeded to accomplish his other object, appointing a place to meet them on his return to the ships. (p. 331)

Unsatisfied with his scouts' reports, Parry sets out himself. Still anxious, as he doesn't yet know the outcome of Ross' trip, he plans to check on Crozier en route

Sep 2

Lyon: Captain Parry now determined on going back in a boat to the eastward of the narrows […] In the afternoon [the next morning? Parry, p. 330: "This night proved the coldest we had experienced during the present season … I left the ships at four A.M. on the 3d"] he set out, taking ten days provisions for his crew, and two for Mr. Crozier, who continued weather-bound. (p. 269)

Parry leaves and encounters hazardous conditions. Trepidation regarding Crozier's fate

Sep 3

Being favoured by a strong north-westerly breeze, we reached the narrows at half-past six A.M., and immediately encountered a race or ripple so heavy and dangerous, that it was only by carrying a press of canvass on the boat that we succeeded in keeping the seas from constantly breaking into her. […] On clearing this, […] the thoughts of all our party were, by one common impulse, directed towards Mr. Crozier and his little boat, which could not possibly have lived in the sea we had just encountered. It was not, therefore, without the most serious apprehension on his account that I landed at Cape North-East, where I had directed the observations to be made on the tides; and sending Mr. Richards one way along the shore, proceeded myself along the other to look for him. On firing a musket, after a quarter of an hour's walk, I had the indescribable satisfaction of seeing Mr. Crozier make his appearance from behind a rock, where he was engaged in watching the tide-mark. I found him and his party quite safe and well, though they had encountered no small danger // [extracted above] // In half an hour after we saw the gig crossing to us under sail, and were soon joined by Mr. Ross, who informed us that he had determined the insularity of the northern land [Ormonde Island, now Simialuk, ᓯᒥᐊᓗᒃ] […] Having furnished our gentlemen with an additional supply of provisions, in case of their being unavoidably detained by the continuance of the wind, I made sail for the isthmus at ten A.M. […] (pp. 330-331)

While Parry continues on his journey, Ross and Crozier make it back together (Parry, returning: "We launched the boat at day-break on the 7th, and on arriving at the narrows, were glad to find that our other boats had left the place," p. 335)

Sep 4

Lyon: Messrs. Crozier and Ross had returned during my absence [a trip to Amherst Island, now Saglaarjuk, ᓴᒡᓛᕐᔪᒃ], and their respective reports were, that the first officer had been unable to make any observations on the tide or current on which he could place any dependence, owing to the prevalence of a strong N. W. breeze, which might in some degree have increased the rapid set continually coming down from the westward: this also prevented his returning on board. He had been picked up by Mr. Ross, who found him in the strength of the current driving fast to the eastward, and was towed on board by the latter, after he had ascertained that the nearest northern shore of the Narrows was an island. (p. 270)

Parry refrains from outright dismissing Crozier's observations and quotes his account

MR. CROZIER'S ACCOUNT OF THE TIDES.

"During the time of our stay at the narrows of the Strait no opportunity was lost of continuing our observations on the tides, an abstract of which is contained in the following Table. By these it will be perceived that in mid-channel the stream constantly set to the eastward from daylight till dark, and that when on the south shore a westerly set was observable, the tide was generally falling. In rowing along the north shore of the narrows, on our return we had a strong westerly set of at least two miles an hour, from thirty minutes after eleven A.M. till thirty minutes after two P.M. on the 3d, during most of which time the tide was ebbing by the shore, and having landed the same evening upon the east end of Liddon Island, we found it high water at seven P.M., being about an hour earlier than the last observed tide in the narrows.

[table, Aug 31-Sep 3]

"From these observations it would appear that the regular stream of flood-tide sets to the eastward, and that of the ebb to the westward, in this Strait; though, at this season, the latter is not always perceptible, on account of the rapid current permanently running against it in an easterly direction." (p. 336)

The next time a tide observation is required, it's Ross who's despatched by Parry

• The expedition, thwarted by the ice in the strait,

retreats and finds harbour at Igloolik. They overwinter together

with the locals, later joined by the Winter Island people. No nearer the goal, Parry devises a Plan B that consists of extending their supplies by sending the Hecla home and continuing for one more year with the Fury (despite the dubious prospects of a strait that only opens

once in a while if ever).

Charity, fishing and Crozier River

|

| "Snow village of the Esquimaux" (source) |

1823

• This winter is notable for an outbreak of illness in the Inuit camp, more severe than the usual complaints. Ann Parry (p. 78) speculates that it's "possibly an infection brought by the

expedition though this does not seem to have occurred to Parry" (Parry's own guess was an overindulgence in meat, p. 413)

Note:

Another thing that didn't occur to Parry was how the Inuit's hazardous lifestyle of non-stop struggles and frequent, sudden loss of friends and relatives might had influenced their overall relationship with death. The expedition went to great lengths to ensure "proper" interment of the Inuit dead (including a couple of sneaky sea

burials).

Parry also overlooked the value of traditional knowledge. While he focused on cleanliness, he also fought against certain "prejudices". According

to the Inuit, "the sick must on no account see each other," and "the

using of a sick person's drinking-cup, knife, or other utensil by a

second individual was sure to be vehemently exclaimed against" (p. 405).

The latter commendable habit was

ended with a threat of a beating.

• The previous year, at the uninhabited Winter Island, the locals arrived late. Here the camps have been in daily contact since autumn, and in December Parry notes that his men in general have become more susceptible to disease. The Inuit start falling ill at the end of January

Feb 2

Having heard also that Innooksioo was ill at the distant huts, I requested Mr. Crozier to call at the village, to endeavour to hire a sledge and a conductor to go out to that station to see him, and, if he wished it, to bring him on board. In this however he did not succeed, the sledges being principally engaged in the fishing, and their owners absent from the huts. Mr. Crozier reporting however that there were still some sick at Igloolik, I went there on the following day [...] (p. 398)

• Soon an Inuit hospital is built beside the ships. One of their more difficult charges, Kaga, is eventually relocated there (she dies the next day)

Feb 21

On the following day Mr. Crozier went out to bring her on board, and on unroofing the hut to remove her to the sledge found, as we suspected, that she had been robbed of almost every thing. (p. 409)

Note:

Parry

was especially fixated on thankfulness and morality. On one specific occasion, he determined that honesty among the locals had dipped beneath Royal Navy standards and decided to make an example of a man who had stolen a shovel. The Inuit, despite returning the tool when confronted, received a dozen lashes on board the Fury (p. 412). Parry was apparently satisfied with the fear instilled.

• The permanent presence of the locals throughout the winter has provided enough occupation for the expedition, so the theatricals were abandoned for good. With the coming of spring the crew are encouraged to play various sports (cricket, football and quoits)

• First signs of a thaw complicate the hunting for the Inuit, necessitating a change of location

Mar 25

Messrs. Crozier and Ross, having spent one or two days in accompanying some of the Esquimaux on their fishing excursions, found that the same floe of "young" and weak ice as before still opposed an insuperable obstacle to the catching of walruses. (p. 418)

• The spring advances, however slowly. On Apr 15 the Hecla's Greenland mate, Alexander Elder, dies after a long illness. On the 20th, Parry commences his Plan B, relocating the supplies to the Fury and issuing a call for volunteers to supplement her crew. The Inuit at Igloolik start to disperse with the change of season

• In May the expedition begins to harvest everything the land provides, as they're no longer able to trade for walrus meat. Several shooting-parties are despatched to hunt, starting with the various birds now arriving. Meantime, low temperatures force Captain Lyon to postpone his land exploration trip to the opposite side of the peninsula. Both captains prospect Quilliam Creek in early June, and later Parry, guided by Toolemak and his wife, leads an experimental fishing-party to the lakes and rivers of that area

Jun 24

[...] we set out together at five A.M. on the 24th, my own party consisting of Mr. Crozier and a seaman from each ship. (p. 437)

• Parry names a local body of water after Crozier – later discovered to be part of a much bigger river

[Jun 30]

The river we were now leaving, and which I named after my companion Mr. Crozier, was about three hundred yards in breadth abreast of our tents; but this part afterwards proved only a small branch of it the main stream coming from the south-eastward along the foot of the hills which Captain Lyon was endeavouring to pass [...] We saw also some brent and snow-geese, and Mr. Crozier obtained a single specimen of the latter. (p. 441)

Note:

The expedition's astronomer, lieutenants, surgeons, purser, clerks and other midshipmen already had assorted features named after them (the Fury's Lt. Nias – islands, Mr Henderson – a point, Mr Ross – a bay, Mr Bushnan – an island; all honoured in 1821). It should also be noted that this time the explorers communicated with the locals, learnt their language and the geographical names. Still, these names were instantly discarded, Igloolik being a notable exception.

Apropos of cultural levelling: "From the perspective of the British imperialist mind of its time, attitudes to the Irish for example, were never, and could never be, about a people who were equal, had a different culture, or could be trusted in a civilised discourse of equals," says Michael D Higgins (source).

Jul 1

Our provisions being now out, we prepared for returning to the ships the following day; and I determined in a short time to send out Mr. Crozier with a larger party, well equipped with every thing necessary for procuring us both fish and deer. (p. 442)

• Upon his return, Parry discovers that Lyon's westward endeavour was aborted. Since the ships are yet to emerge from the ice, Lt. Hoppner travels with the Inuit and later performs more scouting. The duck and walrus hunt continues, as well as the fishing

On the 6th we despatched a party of four men, under Messrs. Crozier and Bird, to the fishing station at Quilliam Creek, equipping them with a trawl-net and every other requisite for obtaining a supply of salmon for the ships. Soon after Captain Lyon, who was desirous of occupying a few days in shooting in that neighbourhood, also set off in the same direction, taking with him a small skin-boat which he had constructed for the use of our fishermen, and which proved of great service in shooting the net across the mouth of the stream. (p. 451)

• Lyon spends some time on his own, trekking, while a fishing and hunting party works in the vicinity

Lyon: On the 14th, I walked to return the visit of our fishing gentlemen, who had called and left a mournful slab of limestone in my tent, on which, beneath their names, was inscribed, "Bad sport—no fish—no deer" but on my arrival I found them in high spirits, the preceding day's labour having procured them about 100 salmon. In this walk I found the river had made such progress in thawing the ice, that it was necessary I should remove as speedily as possible to the fishing-place, lest my retreat should be cut off entirely. On the following morning, therefore, Mr. Crozier, with his whole party, came to assist in removing our baggage, and we reached his tent in safety, though we passed for two or three miles over ice which actually trembled beneath our tread. Fine weather now set in, and proved highly favourable to our fishermen, who in three days caught above three hundred fish, which consoled us all for our former bad success and repeated wet jackets. [...] Our people made use of a trawl in taking the fish, and the little boat was employed in laying it out, and then alarming and driving the salmon into it. [...] I learnt from Mr. Crozier, who had found a snow goose nest, that these birds lay five eggs. (pp. 430-432)

Lyon as quoted by Parry: "Mr. Crozier found the nest of a snow-goose containing five eggs." (p. 461)

Note:

Regarding the Qikiqtaq debris fields, this passage provides evidence of stone messages; elsewhere (p. 272) Lyon also describes some Inuit funeral cairns that only contain scraps of fabric.

Parry: On the 19th Captain Lyon returned from Quilliam Creek, bringing with him the whole of our party stationed there, the ice being now so broken up in that neighbourhood as to render the fishing dangerous without proper boats. On this journey, which it took two days to perform, eleven dogs drew a weight of two thousand and fifty pounds, of which six hundred and forty were salmon, and ninety-five venison, procured by our people. (p. 460)

• Despite these efforts, the health of the men continues to deteriorate, with scurvy becoming unusually prevalent towards the end of July. Parry starts the laborious sawing of the ice to free the ships on Aug 1, and a week later, hastened by the previously deployed layer of sand, the ice starts breaking up. The ships stand out in a couple of days

• Parry consults with his officers regarding the future. The lateness of the season, no positive change in the aspect of the ice, and the poor medical situation on board – likely to be exacerbated by the proposed halving of the expedition – leave them no choice. Parry abandons all his plans in order to preserve lives, and they depart Igloolik on Aug 12, heading home. In the vicinity of Winter Island the Hecla's Greenland master, Mr Fife, dies of scurvy. By the end of September the ships have finally passed Hudson's Strait, and on Oct 10 they anchor at Lerwick, the Shetland Islands.

The third voyage of discovery

In 1824 Parry commenced his final North-West Passage try. The Hecla regained her flagship status, and Crozier rejoined as a midshipman. Still striving for the next career step, he was far more involved with the scientific part of the

expedition. Ross, meantime, had advanced to lieutenant and joined the Fury (in praxis, he was Parry's second throughout both the fitting out and the expedition proper). The objective of this tour was to look for the promising polar waters observed by Franklin, and Parry had identified Prince Regent Inlet as a possible route. However, the first season was once again entirely fruitless, and Parry was forced to winter at a bleak and uninhabited place they called Port Bowen.

On

the morale and entertainment front it was decided that masquerades

should replace the theatre performances Parry no longer thought

appropriate. During the introductory ball on Nov 1 1824,

Crozier appeared in blackface as a lady's footman (Mogg, p. 18).

The third masquerade was held on Feb 2 1825. Among the

"transparencies" (illuminated images) produced for it there was one

showing "[a] rising sun and Polar Bear, with the following motto

We aim at cheerfulness

But when released

We aim at Bear in Straits (Bhering Straits)" (Mogg, p. 24)

Right: "Caricature of Edward Bird, FRM Crozier and GH

[sic] Richards as midshipmen on HMS Fury. Ink

drawing framed, Arctic. By C. Staub." (Royal Geographical Society) [Crozier and Charles Richards

were midshipmen on the Hecla, while Bird belonged to the Fury.]

All hopes of further progress were dashed right at the start of the second season. Both ships were caught in the drifting ice, and the Fury was heavily damaged. Despite the near-inhuman efforts to save her the situation soon became critical. Parry's crucial address to all men assembled on the Hecla's deck has survived thanks to Crozier. Ann Parry notes, "Midshipman Crozier, who preserved these words by copying

them into his little book of orders under the date August 19, 1825,

wrote beneath them: ‘I need scarcely add the ship was ready for sea at

the expected time.’"

|

[1824-5] Salix Arctica [Arctic Willow] Port Bowen |

Two days later they retreated, and the Fury was irrevocably abandoned on Aug 25. Still, all things considered, it

was one of the luckiest disasters in polar exploration, and it also ended up providing a lifeline for one of the future expeditions probing the region.

|

| "HM Ships Hecla and Fury in winter quarters" (source) |

The North Pole voyage

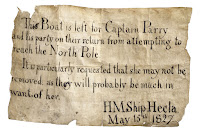

|

| Notice 1827 |

Official instructions

• Parry is to proceed to Spitsbergen; he may make a stop in Lapland to get some domesticated reindeer.

• Leaving the Hecla in a safe harbour at the northern shores of Spitsbergen, the boats are to continue towards the Pole, aiming to return and leave before the winter sets in.

• In the meantime Lt. Foster is to carry out a survey of the northern and eastern coasts of the island. Remaining crew are also to make local scientific observations.

The expedition sets out on Apr 4 and swiftly reaches Hammerfest, Norway.

Apr 19

Finding that our rein-deer had not arrived, I immediately despatched Lieutenant Crozier, in one of our own boats, to Alten, from whence they were expected; a distance of about sixty English miles.

Apr 23

In the afternoon, Lieutenant Crozier returned in the boat from Alten, and was followed the next day by Mr. Woodfall, who brought with him eight rein-deer for our use, together with a supply of moss for their provender (Cenomyce Rangiferina).

A hard gale prevents them from landing provisions at Hakluyt's Headland on May 14, and they enter the pack to escape the swell. They approach Spitsbergen while drifting with the ice eastwards. Beset, they're prevented from landing or setting out on the trek. Ross travels to inspect the floes on May 27.

May 28

On the following morning I sent Lieutenant Crozier, with a small party, to the E.N.E., with the same object; but he had not travelled above four miles, and therefore not beyond the limit of our view from the ship, when the ice beginning to open, I was obliged to recall him.

Parry decides to alter his plan and take only one boat, and they start making sledges.

On the 29th, I sent Lieutenants Foster and Crozier with the greater part of the ship's company, and with a third or spare travelling-boat, to endeavour to land her on Red Beach, together with a quantity of stores, including provisions, as a deposit for us on our return from the northward, should it so happen, as was not improbable, that we should return to the eastward. It is impossible to describe the labour attending this attempt. Suffice it to say that, after working for fourteen hours, they returned on board at midnight, having accomplished about four miles out of the six. The next day they returned to the boat, and after several hours' exertion landed her on the beach with the stores. What added to the fatigue of this service, was the necessity of taking a small boat to cross pools of water on their return, so that they had to drag this boat both ways, besides that which they went to convey. Having, however, had an opportunity of trying what could be done upon a regular and level floe which lay close to the beach, every body was of opinion, as I had always been, that we could easily travel twenty miles a day on ice of that kind.

The delay gets more and more serious, but it's not possible for Parry to leave while the ship is drifting. They manage to land on Jun 6, but the bay is not suitable for harbour. Two days later, they finally escape the ice. Afterwards they reach Low Island, Walden Island and Little Table Island, leaving provisions on the last two. Eventually, on Jun 19 they reach Treurenburg Bay and are able to place the Hecla in a sheltering cove. Parry directs Foster, now in charge of the Hecla, to land the stores in case the ship drifts out to sea and is unable to reconnect with the Pole party.

Jun 21

I left the ship at five, p.m., with our two boats, which we named the Enterprise and Endeavour, Mr. Beverly being attached to my own, and Lieutenant Ross, accompanied by Mr. Bird, in the other. Besides these, I took Lieutenant Crozier in one of the ship's cutters, for the purpose of carrying some of our weight as far as Walden Island, and also a third store of provisions to be deposited on Low Island, as an intermediate station between Walden Island and the ship.

We landed upon the ice still attached to Walden Island, at 3. 30, a.m., on the 23rd. Our flat-bottomed boats rowed heavily with their loads, but proved perfectly safe and very comfortable. The men being much fatigued, we rested here some hours, and, after making our final arrangements with Lieutenant Crozier, parted with him at three in the afternoon, and set off for Little Table Island.

Crozier leaves additional provisions and the requested boat at Walden, as well as an improvised depot at Table Island on Jul 25.

Aug 12

We also found that Lieutenant Crozier had been here since we left the island, bringing some materials for repairing our boats, as well as various little luxuries to which we had lately been strangers, and depositing in a copper cylinder a letter from Lieutenant Foster [...] Among the supplies with which the anxious care of our friends on board had now furnished us, some lemon-juice and sugar were not the least acceptable [...]

Lt. Foster's account reported on the Hecla being forced on shore on Jul 7 (when Crozier was writing his letter to Ross). As per Parry's instructions, after the accident Foster abandoned the plans for extensive survey, and only explored the environs of Waygatz Strait, in order to stay closer to the ship. Expedition left in the end of August, and reached Shetland Sep 17.

The polar trek itself didn't go well. Unusually for

Parry, this time everything – from timing to rations to hardware design – turned

out to be miscalculated, and the weather conditions were also against him. While in his other narratives Parry always points out some kind of silver lining even in the face of a regrettable mistake or a more serious defeat, in the North Pole one he drops the facade. As the "mortifications" multiply – the drift south nullified their murderous crawl north, – the absurdity of the situation gets to him, and he explodes in uncharacteristic exclamation marks. The attempt was not entirely catastrophic only in

the sense that everyone made it back to the Hecla (looking at all the voyages undertaken by Parry, Ross' Antarctic expedition

would experience the same pattern, with the first tour being the most

successful, and the following years paying less and less dividends). That was the end of Parry's active polar career.

On Parry and Crozier

Parry had personally known Crozier since 1821, and they spent three winters together in the Arctic. Additionally, in 1845, as the Admiralty's comptroller of steam, Parry was involved in outfitting the Erebus and Terror with their engines.

Parry writing on Sep 10 1839, after seeing off Ross and Crozier's Antarctic expedition

I took dear Ted [Parry's son] down to Chatham last Thursday to see Ross’s ships before they go, and my old North Polar Companions, now going towards the South. (MS 438/26/398)

Note:

Ann Parry incorrectly quotes from this letter as "my old North Polar Companion [sic]" (p. 212).

However, after the 1845 disaster, he seemingly avoids any mention of his officer Crozier. Parry’s speech at Lynn regarding the Franklin expedition, 1853

But, while we are rejoicing over the return of our friend [Lt. Cresswell], and anticipating the triumph that is awaiting his companions, we cannot but turn to that which is not a matter of rejoicing, but rather of deep sorrow and regret, that there has not been found a single token of our dear long-lost Franklin, and his companions. My dear friend Franklin was sixty years old when he left this country, and I shall never forget the zeal, the almost youthful enthusiasm, with which he entered on that expedition. Lord Haddington, who was then First Lord of the Admiralty, sent for me, and said, ‘I see, by looking at the list, that Franklin is sixty years old. Do you think that we ought to let him go?’ I said, 'He is a fitter man to go than any I know; and if you don’t let him go, the man will die of disappointment!’ He did go, and has now been gone eight years. In the whole course of my life, I have never known a man like Franklin. I do not say it because we believe him to be dead, on the principle de mortuis nil nisi bonum, but because I never knew a man in whom different qualities were so remarkably combined. With all the tenderness of heart of a simple child, there was all the greatness and magnanimity of a hero. It is told of him, that he would not even kill a mosquito that was stinging him, and, whether that be true or not, it is a true type of the tenderness of that man’s heart. (E. Parry, p. 329)

Note:

When James Ross declined to command the 1845 expedition, “Three alternative names came up. Sir John Barrow wanted Commander James Fitzjames […] Lord Haddington, the first Lord, wanted Crozier. Finally, Sir John Franklin, on his return from Tasmania, put in a claim.” (M.J. Ross, p. 247) More precisely, "Captain Crozier was privately offered, by Lord Haddington, then first Lord of the Admiralty, the chief command, but this he declined" (Ross, p. 4). Parry had been friends with Franklin since the simultaneous outfitting of their vessels at Deptford in 1818 (when John Ross and Parry were headed for the NW passage, and Buchan and Franklin towards the North Pole).

Parry's personal life was full of mostly self-inflicted tragedy (exceeding the usual travails of that period). It's perhaps interesting that one of the examples that illustrates his fairly typical 19th c. character concerns the Irish: He felt compelled to organise relief for the suffering Ireland (E. Parry, p. 285), and he was also known

for his memorable impression of an Irishman at charades (ibid, p. 307).

Speaking of Ireland, here's an eyebrow-raising report by Mogg from Port Bowen, 1825

|

[1824-5] Salix Arctica [Arctic Willow] Port Bowen |

Another issue is religion. Parry was not just "pious" (as Ann Parry notes, p. 10, and then deftly avoids the subject), he more or less became a fundamentalist as he aged – his religion was of the Old Testament flavour (everyone is a sinner and should beg for god's forgiveness), and he never shied from demonstrating it. Crozier meantime, as The Polar Museum's blog puts it, was thought by some to be "too poor, too Presbyterian and too Irish" (source). Worse, one could say he fell somewhere between the (soothing) type and the ideal. While not of independent means or an admiral's heir, he wasn't a farmer's boy either – his family was connected and relatively prosperous. As for Crozier's religion, it was human-centric (a person should do their best and hope for god's support). One is bound to remember the church anecdote where the local noblesse surged to the prestigious front pews, while Crozier declared that he's perfectly happy sitting "aft" – "among the labourers and mechanics" (Rev. Pratt, writing a mini version of Parry's 1857 hagiography for Crozier).

One way or the other there's no record of any professional dissatisfaction. Parry had his protege, the high-flying James Clark Ross – and few could emulate him. In 1845 Crozier still held his first Arctic captain in highest regard, proclaiming Parry the only other commander he'd gladly accompany as a second, beside Ross and Franklin.

Sources:

- The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Literature, 1957

- Fluhmann, M., Second in Command: a Biography of Captain Francis Crozier, R.N., F.R.S., F.R.A.S., 1976

- Lyon, G.F., The Private Journal of Captain G.F. Lyon, of H.M.S. Hecla, during the Recent Voyage of Discovery under Captain Parry, 1824 (read)

- Mogg, William, The Arctic wintering of HMS Hecla and Fury in Prince Regent Inlet, 1824–25, in: Polar Record, Volume 12, Issue 76, January 1964, pp. 11-28

- Natural Resources Canada: The Canadian Geographical Names Data Base

- Parry, Ann, Parry of the Arctic, 1963

- Parry, Edward, Memoirs of Rear-Admiral Sir W. Edward Parry, 1857 (read)

- Parry, William Edward, Journal of a Second Voyage for the Discovery of a North-West Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific Performed in the Years 1821–22–23, in His Majesty's Ships Fury and Hecla, 1824 (read)

- Parry, William Edward, Journal of a Third Voyage for the Discovery of a North-West Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific Performed in the years 1824-25, in His Majesty's ships, Hecla and Fury, 1826 (read)

- Parry, William Edward, Letter to Emmeline Stanley (sister-in-law), 10 September 1839, MS 438/26/398;D, SPRI – thank you Olga Kimmins

- Pratt, Charles O'Neil, letter, in: The Macclesfield Courier and Herald, Sat Oct 22 1859

- [Ross, James Clark], A Memoir of the late Captain Francis Rawdon Moira Crozier, R.N., F.R.S., F.R.A.S., of H.M.S. Terror, 1859 (PDF; read)

- Ross, M.J., Ross in the Antarctic, 1982

Illustrations:

- Caricature of Edward Bird, FRM Crozier and GH Richards as midshipmen on HMS Fury. Ink drawing framed, Royal Geographical Society, RGS800459 (image)

- Collection of Arctic plants, Aberdeenshire Council Museums, P3404

- Crozier (Francis

Rawdon Moira), A collection of 36 dried botanical specimens, Bonhams, Auctions 18784, lot 10, & 24633, lot 242

- His Majesty's Discovery Ships Fury and Hecla, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, PAH9224

- Notice 1827, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, AAA3957

Additional resources:

- The North Georgia Gazette and Winter Chronicle: Parry's Arctic newspaper from the first voyage, 1819-1820, published on their return (read | article on the authorship of the anonymous entries as based on a copy annotated by Parry | alternative source to identify the contributors: a copy annotated by William Harvey Hooper, Parry’s purser on the Alexander and the three NWP journeys)

- The music of the original barrel organ used during the expeditions (intro video, the Polar Museum | playlist on youtube)

- Polar Science: Parry’s Arctic Experiments, Royal Museums Greenwich (read)